Coinciding with his solo exhibition at Lawrie Shabibi titled The Lacemaker, Iranian-British artist Farhad Aharania details his array of sources of inspiration, from Hollywood actors to Iranian bazaars and the car-boot sales of Yorkshire.

Interviewed by Zoya Zalatimo - January 2021

There is a range of diverse subject matter that you tackle in your work, from Harper’s Bazaar to Boko Haram and Nassim Aghdam, to Franco Nero- what does that say about your practice?

Everything I make delves deeply into the realm of the personal, verging on the autobiographical. The works are not necessarily about the chosen subject per se, but rather they reflect the way I relate to the subject/person as a vessel or a metaphor for multiple tensions. My aim is to unpack, dissect and re-organise. As such, the chosen subject or object, whatever or whomever it might be, becomes personalised by the way it is handled, considered, treated, or re-positioned. A set of unspoken, abstract, and poetic dynamics are always at play between me as a practitioner/maker and the subject. My chosen subjects might seem disparate or specific yet they always carry universal truths which surpass the physical surface and representation of the work.

What connects these subjects/people within your work?

For me, each and every one of these characters represents a set of entangled, interrupted, failed, or manipulated ideals and desires, which resonate universally. I am fascinated by articulations of daily struggles which lead to empowerment. I have to feel moved in order to apply the taxing task of embroidery onto a surface - to embellish the surface with abstract marks which hint at my own contradictory feelings.

The covers of Harper's Bazaar seduce and transport me back to the fantastical, complex dream-spaces of the Bazaars I roamed around in as a child, and still do to this day, where desires are constantly created and probed. These individual cover depictions are hypnotic, elusive, and escapist. They hint at orientalist fantasies of "The East," which still prevail and distract from the hardcore reality of the bazaar as a place of real commerce and tangible economy.

Similarly, the objectified and sought after body of actor Franco Nero is just another surface and a metaphor for projection and ownership of Orientalist fantasies and ambitions, which still resonate and dominate the realities of our lives in the "Middle East."

On the other hand, Nassim Aghdam's performative endeavours as a young, emancipated Iranian woman living in the United States, having been heavily censored online for her animal rights activism, strongly resonate with me. She represents one person's plight in the face of deception and false notions of personal freedom that are advertised in supposedly democratic, liberal societies.

The idea of manipulation of the truth comes further to the forefront through the images of girls allegedly kidnaped by the extremist group 'Boko Haram'. Contrary to the ‘truth’, images of much older and conventionally attractive women were used by certain media outlets to garner attention and sympathy. Therefore, my hand-stitched series titled 'Boko Haram' refers to the discrepancies around notions of constructed "truths" and facts, which address concerns of misogyny and misrepresentation.

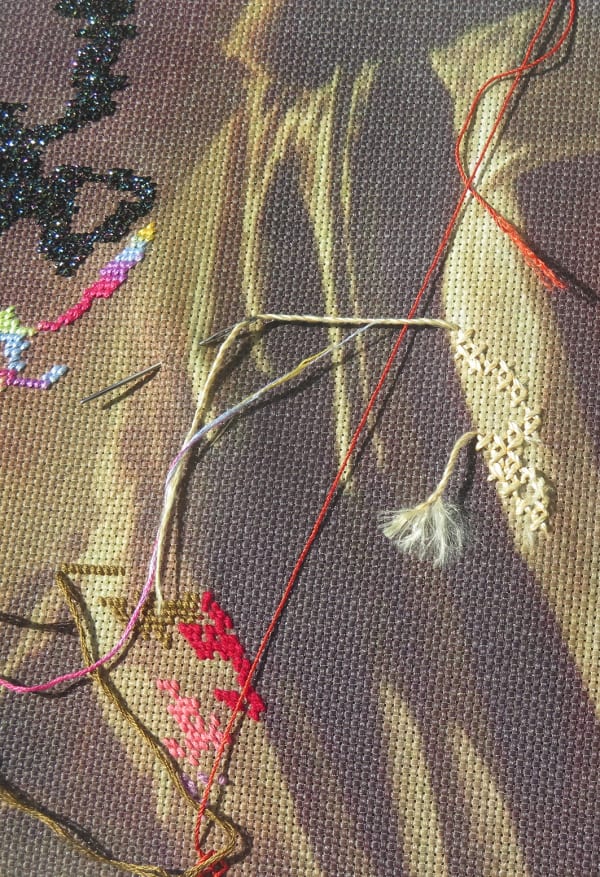

Throughout your works for this exhibition, you have taken an image from a primary or secondary source, such as the internet, then transmitted this onto fabric, which you then manipulated through embroidery. Similarly, the oil paintings are commercial reproductions of original paintings. How do you understand this process of personalizing an image and making it your own?

Through the creation of reproductions a new set of qualities emerges. The applied brush strokes and the painterly marks achieved are slightly more crude, coarse, diluted, overdone or rigid and self-conscious. These qualities speak to an over-compensation to achieve a desired effect, and of being affected, and as such, reiterate the notion of cultural mimicry which never feels "authentic" yet runs rampant in many aspects of our cross-cultural multiple realities. Indeed we are all constantly in a state of selecting and editing images which to some degree entice, challenge, and confirm our status, interests and existential fears and ambitions. Even through the simple acts of flicking through, browsing, and selecting images, some degree of personalisation and ownership is achieved by each and every one of us.

This is the first time we have seen you produce works with oil paintings in this format. You start with paintings done by local artisans, which you then work on top of, sewing in hand-made objects. Where did you draw the inspiration for this series?

The sourcing and the inspiration come from the many car-boot sales that I used to attend religiously in Yorkshire every Sunday morning in freezing cold weather, rain or shine, and the antique shops and the Bazaars of course. In these places the hierarchy of objects is heavily interrupted and reshuffled. The objects appear as though they were thrown up in the air, and have arbitrarily landed on top of one another.

For example, an old embroidery might be found next to a heavy duty tool, or an old painting could be sitting next to a hair-dryer, or a leather belt would be seen lying across the surface of a porcelain dish. These arbitrary couplings and uncanny articulations could be considered subtly surreal, but I am not particularly interested in that aspect. My interest is more formal, because I am intrigued by the sculptural qualities of everyday objects such as nail clippers, pencil sharpeners and combs as well as the painterly qualities of buttons, sequins, and woven items. I also wanted to put more emphasis on other categories of hand made and mass produced utility objects, for their inherently artistic attributes in relation to the privileged position of paintings as a superior cultural product above other visual forms.

Focusing on the commissioned figural oil paintings, which is new to your practice, how do you bring into question Western ideas of authorship and the hierarchy of hand-made objects vs ‘fine art’ paintings?

Almost every aspect of my studio practice is conducted through collaborative means. For the oil paintings, I would always have long conversations over the phone with the sister and brother who produce them for/with me. As such, the paintings are heavily prescribed from the outset. Still, I always look forward to the unexpected results.

I think the addition of a final signature determines the authorship. I am not interested in that aspect, so I never sign the surface of an artwork. What is interesting to me is the quality of the painting as an object, whether it carries a certain degree of charm, naivety or hyper-reality. I think the viewers always bring their own prejudices and judgments onto the surface, judgments which can easily be affected by the aura and the myth created around a particular artist and her/his body of work . The process of confronting a painting and being in its close proximity becomes more of a ritual and a pilgrimage, turning the painting into a fetish, which can overtake any possibility of real and critical reading and appreciation.

I am not trying to elevate the status of the paintings we produce and nor have I any altruistic ambitions to do so. I think they manage to speak for themselves and have their own inner charm, strengths and subtleties, really what I am trying to do is to complicate the position of other hand made objects in relation to painting and the notion of the painterly.

How do gender roles and ideas of domesticity come into play with the items attached to the oil paintings? In her book The Subversive Stitch, which you have cited as a key influence, art historian Rozsika Parker refutes the idea that sewing is a feminine, passive activity. Based on historical evidence of men sewing on the frontlines in both Iran/Persia and England, she argues that "the apparently feminine, domestic practice of needlework is bound up with the masculine and the military." How do you respond to this as a male artist?

In Farsi, the spoken language of my formative years, there is no structure of a 'she' or 'he', there is only one word to refer to the third person. So my way of thinking is not structured around these binaries, in our household these roles were fluid. I have no rigid concept of what defines masculine or feminine. Many women in my family were financially independent and did not subscribe to any specific gendered expectations, and men had interests which might be considered ‘feminine’ if perceived through a Eurocentric lens.

Needle, thread, and fabrics were heavily present in my surroundings, as my parents always had their clothing tailor-made. Certain times of the year called for regular visits to the tailors for fittings. I spent many hours hanging around textile shops while my mother selected fabrics and took samples. The tailors were mostly men, so were the quilt makers and the fabric shop vendors. In the summer of 1976 my maternal grandmother commissioned a quilt maker to make at least 60 handmade king-size quilts for her family. This was the summer of metres upon metres of shiny satins in every colour of the rainbow, except purple perhaps. Actually, the quilt maker moved into my grandmother’s house and worked on the mezzanine level for the duration of that peculiar summer. The impact and impression of that event, a cultural happening in its own right, with its repetitive rituals of cutting, running thread and piercing the surfaces, left a vivid imprint on my memory which I still relish and carry dearly, as if it had all happened just yesterday!